The ground under our feet might look solid, but try stacking up a few hundred kilos of timber, steel, or blocks on it without a solid base and you’ll see just how fast things can go sideways. Even a slight blunder with base calculations could mean cracked walls, jammed doors, or the sort of creaky floors no amount of carpet will hide. At the heart of strong builds, there’s a surprisingly simple but vital formula called the 1 3 rule—the kind of rule no builder in New Zealand or anywhere else should try to dodge. What makes this rule especially interesting is how universal it is—show up at any worksite, from downtown Wellington to the dusty back blocks, and odds are a seasoned tradie will mention it over morning smoko. Ignore it, and you could be looking at shifting slabs or, in worst cases, a foundation repair job that’ll eat your budget alive.

What Is the 1 3 Rule in Construction?

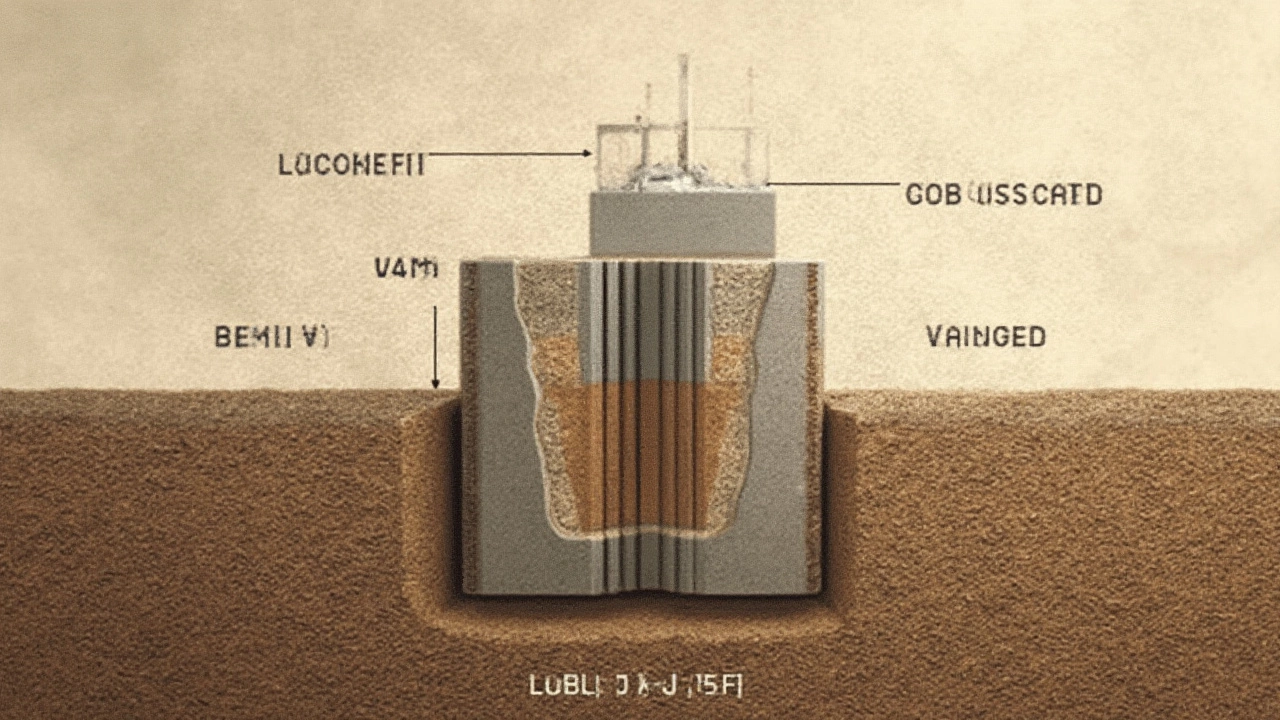

The 1 3 rule is all about footing depth and stability. Here’s how it works: when you lay down a footing—say, for a house or a deck—the part of the concrete sitting above the ground should never be more than one-third the total height. That means the bulk, or two-thirds, of your footing should be below ground, in contact with stable soil. This ratio helps prevent movement and cracking because the earth beneath supports the load, not the loose or shifting topsoil.

This isn’t just old wives’ wisdom either. New Zealand’s building code and practically every reputable construction handbook swear by this ratio because it ties directly into how footings resist forces like heave (when soil pushes up from moisture) or slab settlement (when soil underneath gets compressed). Interestingly, this rule isn’t exclusive to New Zealand—it shows up in Australia, the US, and the UK as well. If you ask three site supervisors from different countries about basic footing design, at least two will likely sketch out this 1 3 method.

This rule isn’t just about compliance—it’s about peace of mind. Nobody wants to revisit a site a year later because the “cheap and cheerful” foundation couldn’t hack a few Wellington winds and rains. If foundations are too shallow or if the above-ground portion is too high, buildings end up moving during extreme weather or quakes. A perfectly poured 200mm thick slab with only 50mm buried is a disaster waiting to happen because the top-heavy design encourages tilting as the ground shifts.

Take decks, for example. The 1 3 rule applies to the posts that support your deck as well. If you go too shallow, the posts heave when frost or moisture cycles hit, throwing your deck out of level in no time. When in doubt, stick with the one-third above, two-thirds below formula—just makes for fewer headaches all round.

Why the 1 3 Rule Matters for Safe, Long-Lasting Foundations

Foundation failures aren’t just annoying—they can be flat-out dangerous. When things go wrong at ground level, you get everything from bulging bricks and cracked plaster to the more serious stuff like shifting entire walls. That’s why the 1 3 rule isn’t just tradition; it’s a proven safeguard. The science is simple: the more of your foundation anchored below ground, the less likely it is to shift when external forces come into play, whether from weather, earthquakes, or even traffic vibrations if you’re building in the city.

Let’s look at some actual numbers. According to BRANZ (Building Research Association of New Zealand), foundations with less than two-thirds of their mass below the ground are over 70% more likely to crack within the first year, compared to those following the 1 3 rule. In Christchurch’s post-quake rebuild, many failures investigated in the Royal Commission’s inquiry pointed to shallow footings that ignored this basic principle. So, this isn’t some obscure theoretical concern—it’s grounded in real-world disaster.

Why does the soil depth matter so much? Soil down deep tends to be more compact and stable, while top layers can be loose, full of roots, or especially prone to drying out or getting saturated. Every time the weather shifts, that top soil layer is the first to move, expand, or shrink. If your foundation is mostly sitting in this "active" layer, it rides with every little wobble, and it’s only a matter of time before cracks show up in unexpected places.

Follow the 1 3 rule, and you’re giving your building a solid anchor, like a fence post dug deep into solid earth rather than stuck in soft sand. This isn’t limited to residential houses either—it’s the same with retaining walls, garden sheds, and those “quick jobs” that seem so straightforward until the ground starts moving. A common story here in New Zealand: someone saves a few hundred bucks ignoring the rule, then two winters later finds their newly installed fence at a 20-degree lean. Cutting corners might save you time, but it never saves you trouble in the long run.

Using the 1 3 Rule: Real-World Tips and Common Mistakes

Now, you might think the 1 3 rule is so basic that nobody could mess it up, but you’d be surprised how often even professionals overlook it when things get busy. The most typical mistake? Pouring shallow pads when the project needs deep piers. It might seem like overkill to go deep for a light garden wall, but Wellington’s legendary winds or New Plymouth’s soggy soils don’t care if it’s “just a little wall.” The earth moves how it wants.

The easiest way to apply the 1 3 rule is to measure the total height of your footing or pier, then make sure only the top third pokes out above ground. The rest? Get it down into stable soil—preferably below the frost line if you’re somewhere that freezes, or below the zone where soil movement is most active. Tools for this are simple: a tape measure, a decent shovel, and a spirit level for good measure.

Here's a handy table with some common footing heights using the 1 3 rule:

| Total Footing Height (mm) | Above Ground (max, mm) | Below Ground (min, mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 300 | 100 | 200 |

| 600 | 200 | 400 |

| 900 | 300 | 600 |

| 1200 | 400 | 800 |

Another tip: always make sure you’re digging down to undisturbed soil—not fill, not old topsoil, and definitely not anything someone dumped there years back. If you hit tree roots or loose stuff, dig a bit deeper. That’s how you get a truly solid base. And if you’re dealing with clay or sandy soils, check your local regulations since you might need to go even deeper or add reinforcing.

Concrete mix also matters. Builders often use a 20MPa concrete for most footings, but if you’re going deep—over a metre—talk to your concrete supplier. They might suggest a quicker-setting mix or an additive for extra strength.

Don’t forget drainage either. Water collecting around your foundation, especially in clay-rich Kiwi suburbs, can weaken the soil around your footing. Simple gravel beds or perimeter drains go a long way to preventing that winter mush that ruins solid work. Think of drainage and the 1 3 rule as best mates for a long-lasting foundation.

The 1 3 Rule Beyond Footings: Other Construction Uses

While people usually talk about the 1 3 rule for traditional house footings, it actually pops up in lots of other places on the build site. Ever wondered why retaining walls have such deep toes (the bit that juts underneath)? Or why building inspectors obsess over deep piles when signing off on decks? That’s the 1 3 principle in action again. It’s also used in concrete post installations, fence building, even precast concrete tilt-panels for big commercial sheds.

Here’s a fun fact: during the rebuilds after the Kaikōura quake, engineers pushed for even stricter ratios, sometimes burying three-quarters of foundation mass below ground. The results: way fewer tilting or shifting issues even after heavy aftershocks. For big commercial projects, like those in Wellington’s CBD, similar principles apply but often with bigger safety margins.

And if you’re a DIY type keen to try small projects, remember this: the 1 3 rule isn’t just for “serious” builds. Even pergolas or letterboxes last longer and move less when you give them two-thirds of their length sunk in firm ground. If you're using anchor bolts or footing cages, keep the exposed bit short—most of the strength comes from what's buried low, gripping soil like a giant hand.

Inspectors love it when they see foundations that follow the 1 3 rule in construction. It saves them headaches, too, since it means fewer callbacks or warranty repairs. So next time you’re pouring a footing, setting a post, or just eyeballing a slab, think about that simple ratio. It’s not fancy, but it’s the unsung hero behind every solid Kiwi home, deck, and fence—and it just works.